On the morning of January 17, 1966, an American B-52 bomber flew over southeast Spain carrying four hydrogen bombs. The aircraft was one of several patrolling European skies with nuclear payloads, ready to retaliate should Cold War tensions escalate. At 10:20 AM, as the B-52 rendezvoused with a fueling tanker, the two aircraft collided, killing seven crewmen and dropping the four bombs over the small farming town of Palomares. Three of the thermonuclear weapons fell onto land in Palomares and were found by the Air Force the next day. With evidence that the fourth bomb might have fallen into the Mediterranean Sea, the Department of Defense brought in Navy salvage forces. If the missing H-bomb was lost at sea, the need to recover it was even more urgent: the law of maritime salvage awarded ownership to whoever found it first.

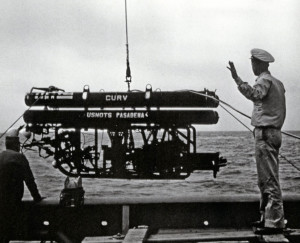

ROV CURV is brought aboard USS Petrel.

By late January, a team led by Navy Chief Scientist Dr. John Craven and Supervisor of Salvage Willard J. Searle Jr. had begun developing a plan to locate the last bomb. They were aided by a Palomares fisherman named Francisco Simó Ortz who led them to an area he had seen a parachute fall into the water on January 17. The Navy brought in a fleet of support vessels, including submarine rescue ships, submersibles Aluminaut and Alvin, and a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) named CURV. More than 150 divers searched the waters for the bomb, but it was much too deep for human recovery. DSV Alvin found it on March 17 at 2,550 feet, lost it during a lift attempt, and rediscovered it on April 2 at 2,900 feet.

This time the Navy sent down CURV, one of the world’s first ROVs. Developed by Naval Ordnance Test Station Pasadena, CURV (cable-controlled underwater recovery vehicle) was designed to recover torpedoes after test runs. As CURV’s operators, working from the deck of submarine rescue ship USS Petrel (ASR 14), attached three lifting lines to the bomb, its parachute tangled with the ROV. Unwilling to lose the bomb again, the operation’s leader, Rear Admiral William Guest, decided to try raising the entwined bomb and CURV together — hoping the connection would hold long enough to reach the surface. The venture succeeded and the bomb was brought onboard the deck of USS Petrel on the morning of April 7, 1966.

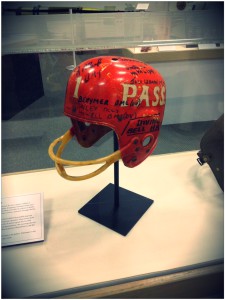

This football helmet (right), in the U.S. Naval Undersea Museum’s artifact collection, was signed by Navy divers assigned to USS Petrel who helped search for the lost weapon. As a submarine rescue ship, Petrel carried a submarine rescue chamber — a device that could lowered to rescue survivors of a submarine accident from a depth of 850 feet. At some point before the salvage operation, a crew member brought the helmet aboard Petrel to wear inside the rescue chamber to protect the wearer’s head from the chamber’s hard steel walls. The running joke among the divers, as they searched for the missing hydrogen bomb during the spring of 1966, was that the helmet would protect them should the bomb detonate.