At the Naval Undersea Museum is a classroom named the Mary Bonnin Room. Mary Bonnin was the first (and currently ONLY) woman who achieved the designation of Navy Master Diver. But few know her full history.

Mary Bonnin joined the Navy in 1976, and eventually completed “A” school to become an Electrician’s Mate (EM). The first woman to successfully complete the Navy Second Class Dive School had just happened the year before: Donna Tobias in early 1975. Bonnin’s first duty assignment was to a dry dock in Norfolk, Virginia, where divers were stationed. At this point, she did not know that the Navy had divers! A billet for the 2nd class dive school in Little Creek, Virginia, became available in 1977, and Bonnin decided to apply for it. After getting numerous stories about the “horrors of it” and “you’ll never make it” from the men in the dive locker, Bonnin decided that heck yeah, she would make it. She tells the story of speaking to her supervisor about the request:

Bonnin joined the Navy in 1976, and eventually completed “A” school to become an Electrician’s Mate (EM). The first woman to successfully complete the Navy Second Class Dive School had just happened the year before: Donna Tobias in early 1975. Bonnin’s first duty assignment was to a dry dock in Norfolk, Virginia, where divers were stationed. At this point, she did not know that the Navy had divers! A billet for the 2nd class dive school in Little Creek, Virginia, became available in 1977, and Bonnin decided to apply for it. After getting numerous stories about the “horrors of it” and “you’ll never make it” from the men in the dive locker, Bonnin decided that heck yeah, she would make it. She tells the story of speaking to her supervisor about the request:

“Baaabe…” (laughs) Right there, I knew this conversation wasn’t gonna go good. He says, “Baaabe, what you wanna be a diver fur? (thick drawl) You’ll never make it. You’ll be back here in a week.” And I – that was probably the point right there where I decided that not only was I gonna go to dive school, but I was gonna become a diver. And he went on and on, and we went back and forth about why I should be a diver, why I thought I should be a diver, and I didn’t know for a while. Finally, they [the command] didn’t have anybody else; none of the guys asked for a billet, so they finally let me go.” [1]

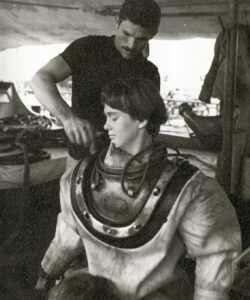

Bonnin graduated top of her class “Honor MAN” and returned to the dry dock, which was being decommissioned. While there she had gotten married and was then stationed in Puerto Rico for about two and a half years with her also-diver husband Ralph. She had her first child Mark (as in Mark Five, the designation for the legendary brass diving helmet/system) diving until her 8th month of pregnancy. Her work there was mostly recovering training torpedoes. Back in the states, she taught at the 2nd class dive school in Coronado, CA, and had her second child, Michael.

In 1982, Bonnin attended 1st class diving school in Panama City, Florida, becoming the first enlisted female diver certified in both air and gas diving in the early 1980s. (Female diving officers had first completed the mixed gas certifications in 1980.) From there she was stationed aboard USS Samuel Gompers, conducting ship’s husbandry work in Alameda, CA (San Francisco Bay Area). While diving under the large aircraft carriers at the base, she developed a method for divers to get to and from the diving area in a much safer and more efficient manner. Aircraft carriers are huge ships, as long as 3.5 football fields, as wide as one football field, and with a 35+ feet depth. It is not easy to find a single inlet or outlet in the hull without some type of road map.

“I also set up a way that we could work underneath the ship and find the hull openings that we were looking for. Because, you know, it’s like being underneath a football field, in the dark, looking for a dime! So what I did was I took the docking plans for the ship and figured out where the tug bollards were, and I set up a plan, and I could drop a diver in a specific place and guide him through hull openings to where he needed to be. And that worked out really well, because we spent half the time we normally would be looking for. . .you know, the tap on the hull just does not work. There had to be a better way to do it, because what we were doing was scary and it was dangerous. And I had to train all the divers on how to properly tag out a ship and how to look at a set of docking plans, and that’s when I really came up with the idea of looking at the docking plan for the tug bollards and figuring it out.”

“[It was important to be able to look] at a set of docking plans and figure out where all the hull openings are and which pumps are to be concerned about, and which ones aren’t, and what needed to be tagged out. So, we did a lot of training with that. And, you know, the kids – the first time I’d send them up there alone, they’d go up and do the tag-out, and they’d come back down to the boat, and they’d say, ‘Okay, chief! I got the tag out done!’ And I’d say, ‘You’re sure?’ They’re, ‘Oh, yeah, yeah! I’m absolutely sure!’ I says, ‘You’re absolutely sure?’ They say, ‘Yup.’ And I’d just kind of give ‘em a skeptical look, and I’d say, ‘Okay, well, suit up. You’re first.’ And probably 60 percent of the time they’d go, ‘You know what? I need to check one more thing.’ (laughs) Because that little thing (laughing) that was sitting on their shoulder, saying, ‘Ooh, should I tell her or not?’ – they needed to go back and check that one. Yeah.”

Bonnin made Chief (E-7) while on the Gompers and deployed to the western Pacific. She wanted a tour on an ARS, but there were only four that had mixed gender crews at the time (1987) and billets were scarce for Chiefs, so she returned to instructor training at the 2nd class dive school in San Diego. Her goal was to go to Master diver evaluations, and several of the Master Divers who were stationed there helped her out.

“They all helped. I mean, I worked my way through teaching all of the courses, which I had taught all of the second-class courses, anyway. Matter of fact, I was the CISO in San Diego – the Curriculum Instructions Standards Officer – in San Diego when I was there, so, you know, I knew all that stuff. And then I finally made it through First Class, and then I was team leader for First Class students and had a lot of help from the Master Divers. They’d ask questions, they’d do drills and all that stuff. So there really wasn’t anything that they were gonna do, short of an asteroid falling into the dive boat, that I wouldn’t have been able to handle. So, I was pretty confident…”

Bonnin went to Master Diver evaluations in 1990, and her selection was by unanimous opinion.

“There was two of us that made Master Diver, and they weren’t supposed to tell you how the vote went, but they told me. They said it was unanimous. And you know, when I went through evals, they were so worried that people were gonna say, ‘Oh, this was bias, you did it just because she’s a woman, blah blah blah…”

DI: “That’s what they always say, even when it’s not true.” (laughs)

MB: “Well, they weren’t gonna say it when I went through. I felt sorry for the other guys in the class because I had – I probably had 140 years’ worth of diving experience on the board. All of them had been in the Navy and they had 30 years or more in the Navy, and most of them had 20 years’ diving experience as a Master Diver. So. They really couldn’t say anything, because anybody who contested it, they’d say, ‘Well, you need to go talk to George Powell.’ And everybody knew George Powell. Or ‘You need to go talk to Shorty.’ And they’d set them straight. Because there was no – you know, ‘She kind of made it.’ (laughs) It was a unanimous decision.”

Bonnin finally was stationed on an ARS, USS Grasp (ARS-51), and became the ship’s Master Diver. Her final tour as a Master Chief (E-9) Master Diver was at the Naval Safety Center in Norfolk, VA. She retired from the Navy in 1996. During her career she trained over one-thousand divers, was a role model and a pioneer, and is still an inspiration to all women divers. So far, no other women have even attempted, as far as I know, to go to the evaluation. As with all things, you will never achieve your goals if you do not try. Failure is an option, but you learn from those mistakes and try again.

“But, you know, the main thing is, is that you need to know that you want to be a diver, and don’t let things get in the way. You know? You’ve got a goal, stick with it, and go for it. And don’t let anything stop you. So, you know. There’s barriers, but you just find a way around them.”

Mary Bonnin was inducted into the first class of the Women Diver’s Hall of Fame in 2000. She continues to inspire and propel others to be their best.

[1] All Mary Bonnin quotes from Darlene Iskra interview with Mary Bonnin on August 23, 2012, in Panama City, Florida.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darlene Iskra has been a volunteer at the U.S. Naval Undersea Museum for 11 years. She started at the front desk as a greeter, and about two years ago she began working in the collections management department, cataloguing collections. She was a naval Surface Warfare Officer and Diving Officer for 21 years, retiring in 2000 as a Commander. She received her PhD at the University of Maryland in 2007, studying the military and society, as well as gender work and family. She started volunteering at the museum to meet new people and give back to the community.