Makakai is a two-man, free-swimming submersible that was developed by the Navy to serve as an oceanographic research vehicle as well as a submersible developmental test and demonstration platform for undersea hardware. It features several unique characteristics that were new technologies at the time, including the first submersible application of cycloidal propulsion, a transparent pressure hull, and the location of most of its control system outside the control module.

The Hawaii Laboratory of the Naval Undersea Research and Development Center (NUC) designed and built Makakai in the late 1960s. It was launched in April 1972 and certified to 600 feet in July. In August, Makakai Project Engineer Douglas Murphy and Sealab co-leader Dr. Walt Mazzone were certified as pilots. At the time it was developed, Makakai was NUC’s deepest-diving certified submersible.

The development of Makakai brought together several programs based at the NUC Hawaii Laboratory, including the development of transparent pressure hull materials, cycloidal propellers for submersible propulsion, a through-hull or soft-line information transmission system to eliminate or reduce the number of penetrations required in the pressure hull, and pressurized electronics. Makakai was developed specifically to demonstrate and evaluate these program systems, and to create a functional submersible from which observations and tests could be conducted.

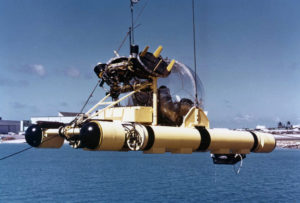

Makakai’s name, meaning “Eye in the Sea” in Hawaiian, referred to its 66-inch clear acrylic sphere. At 2.5 inches thick, it served as the vehicle’s pressure hull and could hold two operators. The sphere, made of two spherical pentagons bonded by adhesive, had a design depth of 1000 feet with a collapse depth of 4,200 feet. The transparent sphere offered its occupants an unobstructed, panoramic view of the submersible’s surroundings. It was mounted to two parallel pontoons that housed batteries and ballast tanks. A variable ballast system supplied buoyancy control to the submersible. Ballast tanks located on each corner of the vehicle provided buoyancy trim, pitch trim, and roll trim.

Two Kirsten Boeing bi-pitch cycloidal thrusters, mounted above and aft of the pressure hull, provided the vehicle’s propulsion. With only those two propellers, the cycloidal propulsion system furnished all the degrees of propulsion control normally obtained by four or five screw thrusters. They operated like paddle wheels, generating thrust by moving the individual blades on the propellers with respect to the water. Thrust direction was varied by changing the relative phasing of the blades with respect to the disc. A four-horsepower hydraulic motor drove the propellers. Makakai’s top speed of three knots typically translated to a practical speed of 0.75 knots.

Many of Makakai’s control electronics were located outside its pressure hull in ambient pressure housings. Signals for routine controls (lights, propulsion, ballast system) were transmitted over a single, optical path from the sphere’s interior to exterior. This advantageous design eliminated penetrators and the problems that could accompany them. It also provided more usable room within the sphere and reduces the amount of heat inside it, which could obscure visibility by creating fog.

Makakai was completed in 1971 and underwent sea trials off San Clemente Islands in September 1971. It was transferred to NUC’s San Clemente Island test range in August 1972 and became operational two months later in October. Problems soon arose with its multiplex system, the electrical systems that controlled its external functions. Makakai returned to San Diego for modifications, but the multiplex problems proved insoluble and the submersible was dismantled in September 1973. It was transferred to the U.S. Naval Undersea Museum in 1987.