Man of Honor: The Story of Carl Brashear

Born into a sharecropping family in 1931, Carl Brashear rose from little to become the first African American Master Diver and first amputee diver in the U.S. Navy.

Brashear’s path to success was difficult and unlikely given the many obstacles that barred his way. With determination and persistence, he overcame those challenges to fulfill his dream of becoming the first African American Master Diver. Today, more than 15 years after his death, Carl Brashear is a household name following the popular success of “Men of Honor,” a 2000 Hollywood movie based on his life. For many, he has come to represent the power of perseverance and resilience.

This exhibit follows Master Diver Brashear’s journey from a young African American teenager in segregated America, to a highly successful Master Diver and master chief in the United States Navy, to the legacy he created in life that now continues beyond his death.

Continue reading to experience this online exhibit, or use these links to jump to specific pages:

> Early Years (1931–1950)

> I’ve Got to Be a Deep-Sea Diver (1950–1966)

> Catastrophe Strikes (1966–1968)

> Making Master (1968–1979)

> An Enduring Legacy (1979–present)

> Timeline: An Extraordinary Life

Childhood on the Farm

Carl Maxie Brashear was born on January 19, 1931, in Tonieville, Kentucky, to parents McDonald and Gonzella Brashear. At just six weeks old, he moved with his family to a farm outside the town of Sonora, where his father worked as a sharecropper. He lived there until age 17, assisting his father with chores like milking cows and chopping wood.

The large family, which included eight children after a sister died in infancy, cultivated close bonds during their years on the farm. Although poor, “we didn’t know much about it. We thought that was a good way to live,” Brashear later reminisced. They enjoyed plenty of food grown on the farm, and “we had a lot of love in our family, a lot of togetherness.”

In his off time, Carl sought out “exciting, daring things” like riding a motorcycle at age 13 or skipping church to go swimming. This love of adventure would continue throughout his lifetime.

A Segregated Education

From first to eighth grade, Carl attended a segregated, one-room schoolhouse “with broken-out windows and hand-me down books.” His experience mirrored that of his parents, whose educational opportunities had ended at ninth grade (Gonzella) and third grade (McDonald).

The school for African American students was located three miles away in Sonora. Carl woke before dawn to carry out his chores before walking to school each day. At home, his mother supplemented his classwork by teaching extra math and dispensing reading assignments from magazines and newspapers.

While a good student, Carl disliked school. He felt he didn’t need an education. After finishing eighth grade, he declined to enroll in high school.

“When I was about five or six years old, when we would be walking to school in the sleet and the mud and snow, the white kids would be riding the bus. That’s when I realized what was going on….that there was prejudice.”

Joining the Navy

By age 14, Carl decided to follow in the footsteps of his brother-in-law, who served as a solider in the U.S. Army. He tried to enlist in 1948 when he turned 17, but he failed the Army entrance exam after becoming rattled by abrasive treatment from the test’s proctors.

On the way home from the disheartening experience, Brashear passed a Navy recruiting office and stopped in. The recruiter he met spoke so glowingly of the Navy — and so kindly to Carl, in sharp contrast to his interaction with the Army proctors — that Brashear chose to join the Navy instead.

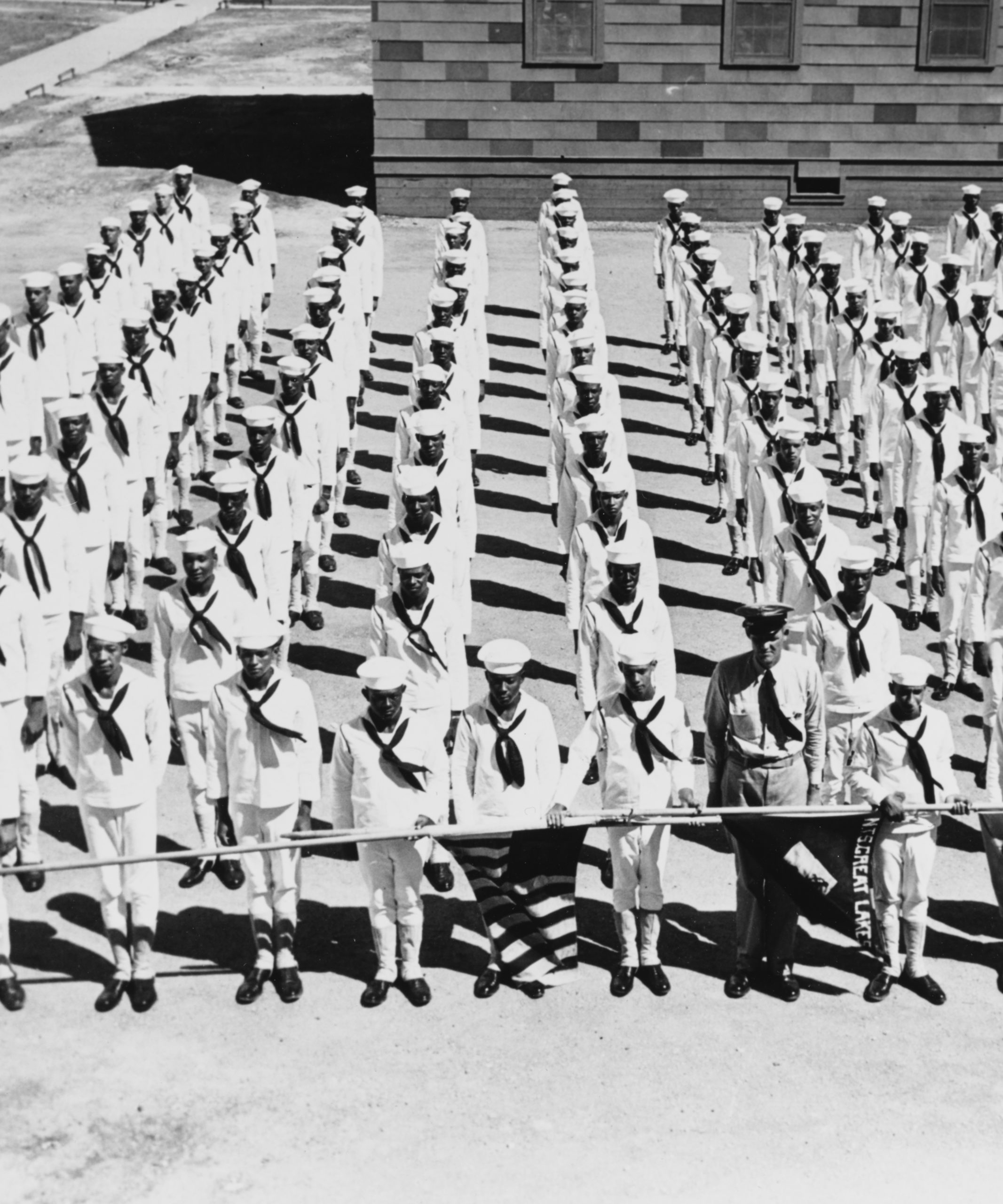

From February to May 1948, Brashear attended basic training at Naval Training Center Great Lakes. Brashear served in an integrated company and felt he was treated equally during these months at boot camp.

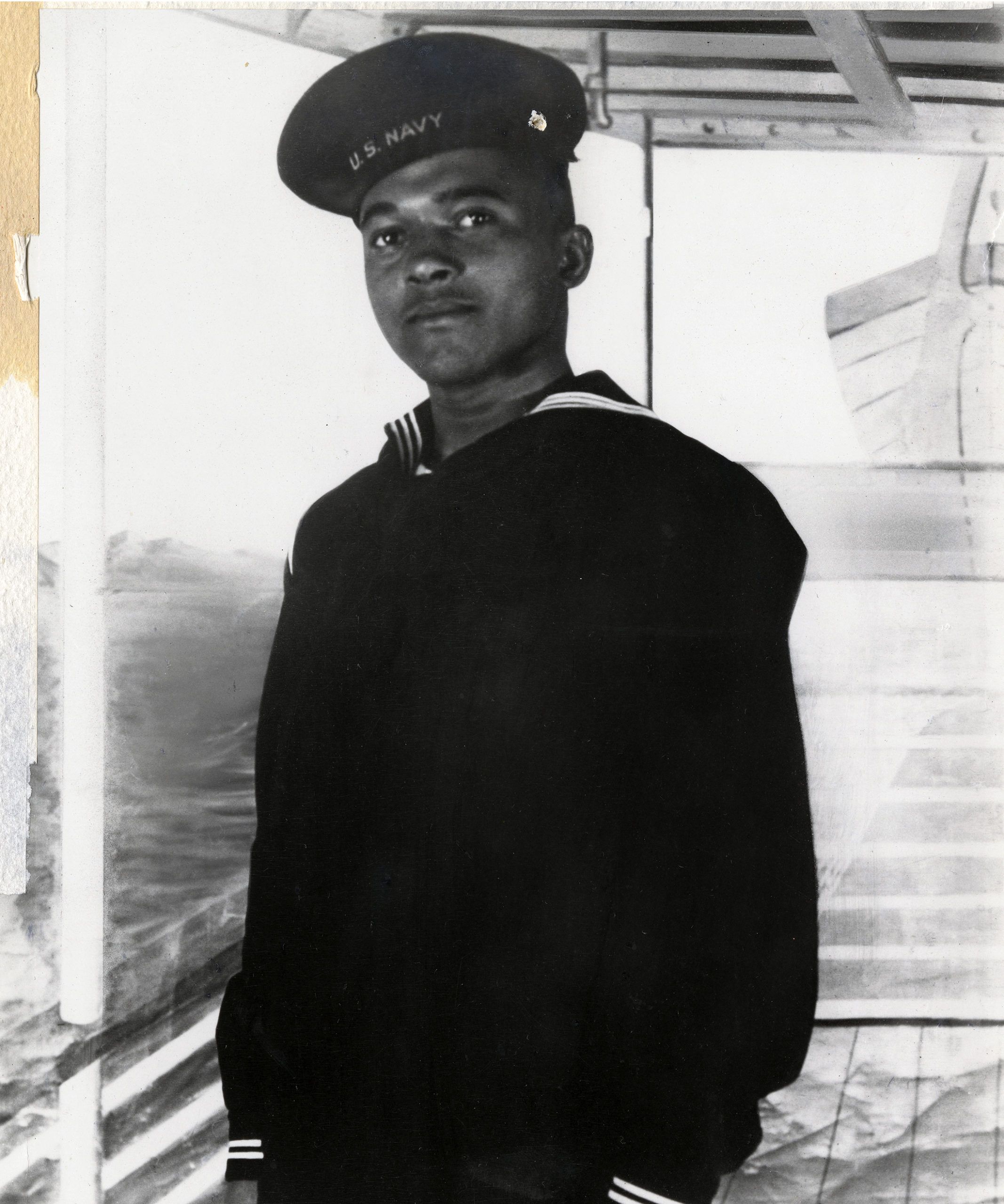

Service as a Steward

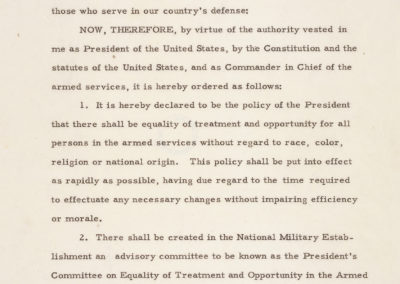

Between the 1890s and the 1950s, the Navy alternated between barring African American Sailors from service and segregating them in positions as messmen, stewards, and cooks. President Harry S. Truman’s executive order officially integrating the U.S. Armed Forces — issued in July 1948 — came two months too late for Carl Brashear, who completed boot camp and began service that May.

Brashear served for one year as a steward, during a two-year assignment at Experimental Squadron One in Key West, Florida. He engineered his exit from the steward branch by befriending and impressing Chief Guy Johnson, who arranged for Brashear to transfer ratings to boatswain’s mate. In his new rating and role, Brashear worked as a “beachmaster” launching and recovering seaplanes from the beach.

By the time Brashear finished his tour at Squadron VX-1 in June 1950, he had advanced to third-class boatswain’s mate.

Executive Order 9981: “It is hereby declared that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.”

Brashear helped launch and beach two Martin PBM bombers. The work involved a great deal of swimming, which Brashear loved.

“I learned how to get along with people, how to respect other people, and to do my job without somebody coming around watching me quite a bit. I developed an attitude that, ‘I’m as smart as you are, and all I have to know is what you want me to do, and just let me do it.’ I didn’t have that type of attitude in the steward branch, because I didn’t think I should be shining shoes and waiting on officers.”