An Enduring Legacy (1979–Present)

Life After the Navy

Carl Brashear needn’t have worried about succeeding in civilian life. Nineteen days after retiring, he was offered a job by a former boss, a retired Navy captain. Brashear agreed and executed a $6 million diver study for the Royal Saudi Navy.

In 1980, pain from slipped vertebral discs forced Brashear to undergo back surgery. (He tried to leave hospital just four days later, always ready to return to life and work.) The doctors told him he likely could no longer jog, lift weights, or exercise. Brashear’s response? “You fixed me, didn’t you, Doc? Well, I’ll do the rest.”

Brashear pursed additional education over a period of 18 months, taking college courses in environmental science. The training led to a 10-year tenure as a specialist in environmental protection and energy conservation at Naval Communication Area Master Station Atlantic. With his usual drive, Brashear outperformed expectations, and grew his job by seven promotional levels and considerable responsibility.

At age 62, Carl Brashear retired from his civilian career, planning to enjoy whatever time he had remaining: “My goal is to get up and be happy every morning. That’s my plan for the future.”

“I came to [Naval Communication Area Master Station Atlantic] with the old “can-do” spirit. I was told when I reported in here that this job would never be anything but a [level] GS-7. I said, ‘Well, we’ll see.’ So I initiated things, initiated programs, wrote my own [position description] on several occasions to let the people know what I do….You’ve got to tell people what you do and what you accomplish.”

Legacy Assured: “Men of Honor”

The 2000 movie “Men of Honor” made Carl Brashear a household name. Brashear petitioned Hollywood for 20 years to get the film made. Eventually, his story caught the attention of producer Robert Teitel and director George Tillman Jr. The pair spent a week interviewing Brashear in his Virginia home and decided his story had to be shared. “Men of Honor” traced Brashear’s Navy journey from his efforts to attend dive school through his hard-fought return to diving following his amputation. Actor Cuba Gooding Jr. starred as Carl Brashear and actor Robert DeNiro played a composite of several instructors Brashear knew during his career. Although some details were changed, Brashear felt the finished film portrayed his experiences with good accuracy.“I knew this story would inspire people if it was ever shown on the big screen. It’s powerful to see what one individual can accomplish if he works hard and has a good attitude.”

Mourning a Legend

Master Diver Carl Brashear died of heart and respiratory failure on July 25, 2006, at the Naval Medical Center in Portsmouth, Virginia. His family was with him when he died, including his son Phillip, an Army warrant officer who flew home from Iraq on emergency leave to be at his father’s side.

Tributes poured in to honor a man who had achieved so much and inspired so many. Chief of Naval Operations Michael Mullen remembered him as “the very best of men…. [he] made us all better, and we — as a Navy and as a nation — are going to miss him sorely.” Actor Cuba Gooding Jr. called him an inspiration and “the strongest man I ever met.” Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy Joe Campa Jr. would reflect that “the character of our Navy changed the day Carl Brashear decided nothing was going to stop him from pursuing his dreams.”

Carl Brashear’s funeral was held on July 29 at Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek — the same base at which he had retired from the Navy 27 years earlier. More than 800 people attended to pay their final respects. He was buried at Woodlawn Memorial Gardens in Norfolk, Virginia, with full military honors.

A sailor prepares to fold the American flag that draped the casket of Carl Brashear during Brashear’s burial service.

“Carl, a man with such humble beginnings, touched so many people. He represented African Americans. He represented people with disabilities. He represented the United States Navy. He represented veterans. He was the best of the best of what was truly American.”

Like Father, Like Son

Carl Brashear’s influence ranged far and wide — and close to home. He modeled resilience for his four children, refusing to let them say they couldn’t do something. “In our household, it was either ‘I will’ or ‘I’ll try,’” remembered his son Phillip.

Inspired by his father, Phillip chose to join the Army Reserves in 1981. He has served almost four decades in the military, piloted helicopters for 27 years, qualified as a Master Army Aviator, and reached the rank of chief warrant officer 4.

Today Philip Brashear works to keep his father’s story alive. He and his brother DaWayne started the Carl Brashear Foundation to inspire others through their father’s attitudes and achievements.

Phillip’s son, Tyler, decided to carry on the family tradition of military service begun by his father and grandfather. Tyler is currently a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) cadet at North Carolina A&T University.

Phillip Brashear currently serves as the command chief warrant officer for the Army’s 80th Training Command.

“If [my father] hadn’t passed down the ethic of never giving up, I wouldn’t be where I am today. It is something to be the son of Carl Brashear because for the rest of my life there is nothing I can give up on. I will always have to achieve to make something out of myself, because that is what he did.”

More History-Making Master Divers

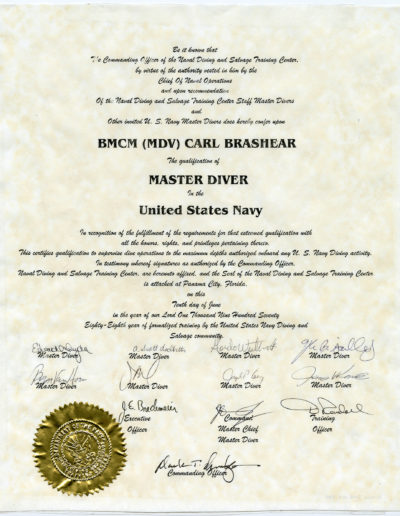

Carl Brashear became the first African American Master Diver in June 1970. Since his historic achievement, at least four other African American men have earned the elite designation.

Master Chief Boatswain’s Mate John B. Davis rose through the diving ranks at the same time as Carl Brashear. The two men pushed each other to work harder, as both vied to make master diver. Davis qualified in 1972 to become the second African American Master Diver.

Six years into his 26-year Navy career, Master Chief James Joseph “JJ” Fenwick Jr. transferred to the diving community. He took part in three pivotal search operations in the 1960s: the missing hydrogen bomb (1966) and the searches for missing submarines USS Thresher (1963) and USS Scorpion (1968). Fenwick became a master diver in October 1975. He went on to commission as a chief warrant officer and to serve as executive officer of USS Elk River (IX 501). Fenwick retired as a lieutenant in 1985 and died in 2018 at age 77.

Master Chief Hull Maintenance Technician Michael J. Washington enlisted in 1973 and began dive school in 1975. After being selected for the master diver evaluation, he suffered a stroke that shut down one region of his brain. While still healing, he qualified as a master diver in January 1992. A second stroke ended his ability to dive, but he continued serving in the Navy as the Leading Fleet Master Diver and the first Force Master Diver at Commander, Naval Special Warfare Command. Washington retired in 2003 with 30 years of service.

Master Chief Navy Diver J. Lamont King qualified as Master Diver in September 1995. After retiring, he spoke at Carl Brashear’s funeral service in 2006.

USNS Carl Brashear

In 2008, the Navy honored the service and achievements of Carl Brashear by naming a ship for him. USNS Carl Brashear (T-AKE 7) is 689-foot dry cargo/ammunition ship operated by the Military Sealift Command.

The ship was christened and launched on September 18, 2008, in a large ceremony celebrating its namesake. “USNS Carl Brashear embodies the spirit and character of this remarkable individual,” Chief of Naval Operations Gary Roughead proclaimed at the event. “[Naming the ship after him is] an affirmation of our values and those of Carl Brashear. I could not be more pleased to have his spirit in this ship.”

Many of Carl Brashear’s family members attended the launching. His eldest granddaughter, Lauren Brashear, served as the ship’s sponsor.

USNS Carl Brashear entered service in March 2009.