Book Review | Total Undersea War: The Evolutionary Role of the Snorkel in Dönitz’s U-Boat Fleet, 1944 – 1945

Reviewed by Charles R. Gundersen, museum volunteer

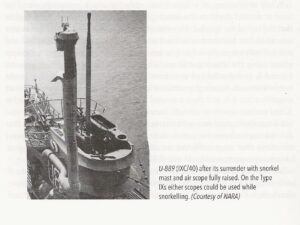

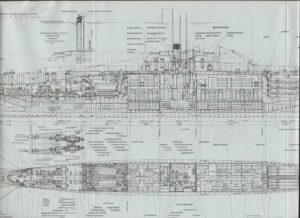

This book (Figure 1) is a double monograph due to both its time frame and its subject matter. It discusses just one item, the submarine’s snorkel, and covers a time span of just one year (late 1944 to early 1945). The U-boat’s snorkel (Figure 2) was a new device used to pull fresh air into the submarine for use by the crew and diesel engines. After a brief discussion of the early submarine war in the Atlantic Ocean in World War II, the author spends the first half of the book detailing the technical details of the snorkel. The second half of the book tells about the operational patrols conducted by U-boats with snorkels (mainly the Type VIIC and IX).

|

|

Figure 1 – Title Page |

|

|

Figure 2- Snorkel Mast Installed on Type IX U-Boat |

The author begins the story in April 1944 with snorkel testing in the English Channel and the hope the snorkel would allow the U-boats to renew their commerce raiding in the middle of the Atlantic and renew their offense along the U.S. Atlantic coast. Morale and optimism for success were high. One could say the snorkel was “transformative.” And the author states in several places the snorkel fundamentally altered the nature of submarine warfare. And the snorkel-equipped U-boats, as a naval force, were never defeated; since new U-boats were constantly replacing the ones sunk throughout the war. However, snorkel equipped U-boats were totally unable to fight off the Allied invasion of Normandy in June of 1944 as Dönitz had hoped.

The book is mainly a fact book; it is not a story book nor is it a “what-if” book. The submarine operations detailed in the last half of the book relate the actual experiences of various U-boats practicing “Total Undersea War.” There is no speculation of what could have been accomplished with this new capability. The book discusses the next (and last) steps the Germans took in prosecuting the undersea war in the Atlantic Ocean.

In general, the book tells you all you ever wanted to know about how the Germans developed, installed, and used the snorkel. I never realized just how many U-boats were equipped with the snorkel: All 353 of them are listed in Appendix A. From this number, we can see the snorkel did function as designed mainly on the Type VIIC and IX; and it was working right up to the last day of the war at sea. The author noted the U-boats (and “V” rockets) were the only major weapons remaining operational at the end of the war. Even German propaganda blasted that rockets would soon be installed on, or towed by, U-boats that would be coming toward New York City. Another combination of weapon systems worked on late in the war combines the snorkel with the Walter gas turbine engine, which today would be called “Air Independent Propulsion.”

Somewhat off the subject, the author has chapters on both anti-aircraft radar protection devices and the anti-sonar acoustic camouflage techniques of rubber coating being applied to the entire submarine outer hull. He ends this discussion with the fact that no U-boat with an anti-sonar rubber coating and a snorkel was ever sunk by Allied anti-submarine patrols. According to the author, even U.S. intelligence services “began to see the snorkel as a success.”

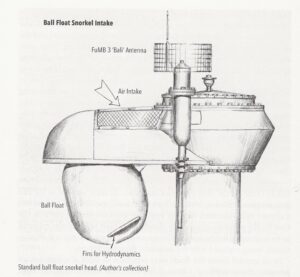

Some of the drawings show the snorkel head and the details of how it functioned and how it was deployed. However, I would have liked to have seen more details of the valving within the snorkel head (Figure 3). Other drawings in the book show how the snorkel was installed on the Type VIIC and Type IX U-boats and plans for installations on future U-boats. This is where I had a problem, as the “elephant-in-the-room” was TIME. It had expired and there were no future German submarines to benefit from the next generation of snorkels.

|

|

Figure 3 – Snorkel Head Showing “Bali” Radar Detector |

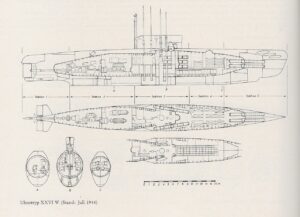

I found Chapter 5, Electro/Hydrogen Peroxide-Powered U-Boats, to be most interesting. The author argues that it was the very-late war Type XXVIW (Figure 4), and not the Type XXI, that was considered the next evolution in U-boat design. Oddly enough, the main reason for this was the extensible snorkel in the Type XXI. It was the boat’s Achilles heel.

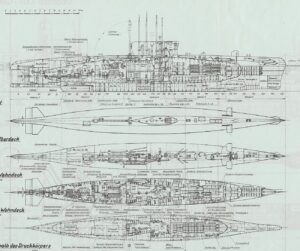

Note, it was the Type XXVIW the Allies used as a model for their next generation fast attack submarine, not the Type XXI. Maybe Clay Blair was correct in his criticism of the Type XXI, as its snorkel was an afterthought and was installed when the submarine was in its bombproof pen preparing for its first patrol (Figure 5). Note: All U.S. Navy nuclear powered submarines were designed to accommodate snorkels. The earlier U.S. Navy diesel-electric boats had their snorkels installed as part of their Greater Underwater Propulsion Power (GUPPY) upgrade.

The author, also, had very little praise for the Type XXI. In the race for underwater speed, the snorkel never helped the Type XXI, even though it had an advertised underwater speed of 24 to 25 knots. But when completely submerged and retrofitted with the snorkel, the top speed was reduced down to about 13 knots. Even this lower speed led to excessive vibrations of the snorkel and periscope, so the top speed was further reduced to just 6 to 8 knots (comparable to the speeds of the Type VIIC and Type IX). Now, try to charge the batteries and the speed further reduces to around 2 to 4 knots. So, no improvement here. Luckily, the snorkel allowed submerged operations to last for several months.

|

|

|

Figure 4 – The Type XXVIW (Source: Bottom Drawing Uboottyp XXVI – Generalplan. by Fritz Köhl |

|

|

Figure 5 – Midship Section of Type XXI Showing Extensible Snorkel Location (Source: Drawing Uboottyp XXI – Generalplan 1. by Fritz Köhl) |

The author goes over some of the benefits to be derived from operating submerged with a snorkel:

The snorkel allowed the U-boats to transit to their operating area using their diesel engines while completely submerged and hopefully free from detection by radar. Once far out to sea in their operating area, they were allowed to operate more independently (not in a pack, as before) without reporting back to Admiral Döenitz. It was possible to recharge the submarine’s batteries as well as provide power to the propulsion system.

At the outset, and almost overnight, there were fewer communications with submarine command (Döenitz) back on the mainland. This led to fewer radio interceptions by the Allied spy network and provided ULTRA with little to decode. Plus, there was less tracking by the Allies using their high-frequency radio direction finders.

The snorkel also provided fresh air for the crew and air to recharge the air flasks.

The snorkel allowed the submarine to hide in shallow water near the enemy’s coast rather than having to dive deep and hope they were below the set depth of the oncoming depth charges.

The U-boat loss rate due to Allied ASW operations showed a decrease compared to the 1941 / 1942 loss rates. The author points out just how successful the snorkel was, as it allowed submarines to operate far from their bases in Norway.

And, of course, the author points out some disadvantages:

Short Wave and Very Low Frequency radio signals were difficult, if not impossible, to receive while submerged.

A slow submarine submerged speed of about 6 knots (mainly due to snorkel pipe and periscope vibrations) was the only speed possible. But the submerged speed, using only the batteries, was less than half that speed. The exposed frontal area of the snorkel mask and exposed air and exhaust tubing created a large drag force on the submarine, further retarding its speed. However, surface speed with diesels was about 17 knots.

Closing the snorkel’s float valve due to wave action caused a rapid loss of air pressure within the hull producing severe eardrum pain among the crew. It was best to leave all interior compartment hatches open to provide a large volume of air to draw upon when the float valve closed.

Carbon monoxide poisoning or oxyhydrogen gas explosions were always a threat.

Due to weeks of completely submerged operations in salt water, the deck guns and some interior electrical and communications equipment no longer worked.

Most snorkels were installed after the submarine was commissioned. The work was not quite a “hatchet job,” but it suffered from not being integrated into the total submarine design. The snorkels were installed as a refit so as not to interfere with the hurried construction schedule. The author relates stories where submarines had to sail from the building yards in Germany without a snorkel to the submarine fitting out pens on the west coast of France (Bay of Biscay ports) where the snorkels were (mostly?) installed. Then they transited to the bases in Norway to correct any snorkel installation deficiencies, conduct deep diving tests, and, finally, to prepare for operations at sea.

I thought the book provided an excellent and thorough coverage of the snorkel and I would definitely recommend it. If you are interested in the technology of the snorkel, study Part I. If you want to read war stories, read Part II. Read Chapter 1 in any case. And don’t miss reading about the fate of U-869 in Chapter 10, as this version of the U-boat’s demise differs from the usual story as re-told by Clay Blair in Hitler’s U-boat War, Volume II, page 651.

There is more I could say about this book but I think this report is long enough. All that is left for you to do is to pick up this book and read it.

The Take-Away: It became obvious that a submarine that didn’t surface and didn’t transmit radio signals was almost impossible to track, locate, and destroy. With this concept, one can be successful at “Total Undersea War.”

Question: Even if the snorkel equipped U-boats had successfully stopped all trans-Atlantic commerce, would that (by itself) have been a war-winning effort?

I may not have served on board a submarine (as I spent my active duty years aboard a large “target,” USS MIDWAY), but I have had an interest in submarines since building plastic submarine models in junior high school. I got my fill of submarines as a short-term rider on over a dozen SSN 688 Class submarines while tending to my recording equipment when I was a civilian employee of the Navy.

|

|

Figure 6: Testing, Testing, and More Testing (The answer is in there somewhere) |