Catastrophe Strikes (1966–1968)

A Life-Threatening Accident

Post-dive school, Carl Brashear spent a year aboard the fleet tug USS Shakori (ATF 162) before requesting a transfer to the salvage ship USS Hoist (ARS 40) in September 1965. Serving on Hoist would help him to earn qualifications needed to become a master diver.

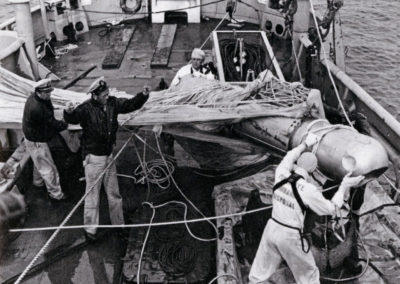

In February 1966, the Navy sent Hoist and her crew to Palomares, Spain, to help search for a hydrogen bomb. The thermonuclear weapon had fallen into the Mediterranean Sea after two U.S. Air Force aircraft collided the month before. The United States urgently needed to recover it before another nation could.

On the afternoon of March 23, as Brashear directed the transfer of a crate to hold the bomb once found, the supply boat parted its mooring line. Brashear rushed to get his Sailors to safety. A steel pipe broke loose, flew across the deck just as Brashear pushed a Sailor out of the way, and struck Brashear. The blow critically injured his left leg.

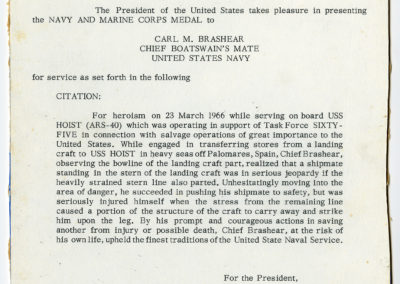

The Navy would later award Brashear the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his heroism that day. His quick action saved the Sailor’s life — but put his own in jeopardy.

“They said I was way up in the air just turning flips [from the impact of the pipe]. I landed about two foot inside that freeboard. I jumped up and started to run and fell over. That’s when I knew how bad my leg was.”

Carl Brashear’s Navy and Marine Corps Medal citation. The medal is the highest peacetime award for heroism, and recognizes “personal life-threatening risk” to the recipient.

The Fight to Survive

USS Hoist’s corpsman sprang to work, placing two tourniquets on Carl Brashear’s leg. Brashear was transferred first to nearby ship USS Albany (CG 10), and then to a helicopter for an emergency medical evacuation.

Four hours after the accident occurred, Brashear and a doctor from USS Albany found themselves stuck on a runway in Spain awaiting another aircraft. Brashear went into shock from severe blood loss and passed out. The doctor later admitted he believed Brashear would die.

By the time Brashear arrived at the emergency room at Torrejon Air Force Base, he had no pulse or heartbeat. Medical staff managed to restart his heart and administered 18 pints of blood before he regained consciousness and stabilized.

He was eventually transferred back to the United States to the Portsmouth Naval Hospital in Virginia.

Road to Recovery

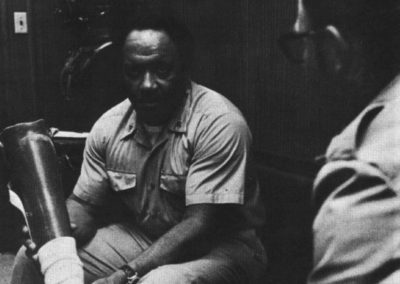

Although alive, Brashear had suffered severe compound fractures to both bones in his lower left leg. Doctors told him his injury would take three years to heal and that walking again would likely require a brace.

Brashear asked them to amputate, unwilling to wait years: “I can’t be tied up that long. I’ve got to get back to diving.” His leg became so badly infected they agreed, amputating below the knee on May 11, 1966. A second surgery performed in July removed another inch and a half from his leg to fully eliminate the infection.

As he recovered, Brashear researched. He read about an amputee pilot in the Canadian Air Force who had returned to flying. He discovered the capabilities of prosthetics. And he learned the importance of a positive mindset in accepting his amputation and finding new solutions.

In early December, he received his first prosthetic leg. (The leg was painted to match Caucasian skin, a reminder of the inequality afforded to African Americans.) Brashear immediately gave up his crutches and began adapting to his prosthetic limb.

“It took more willpower than I ever thought I had, to accept the fact that I had lost a leg. Once I accepted that, I knew I would win the fight to become a master diver.”

An Uphill Battle: Returning to Full Duty

True to his resilient nature, Carl Brashear was determined to dive again. He convinced the Navy to return him to Portsmouth Naval Hospital to be near the Norfolk diving school, headed by an old friend from salvage school, Chief Warrant Officer Clair Axtell Jr.

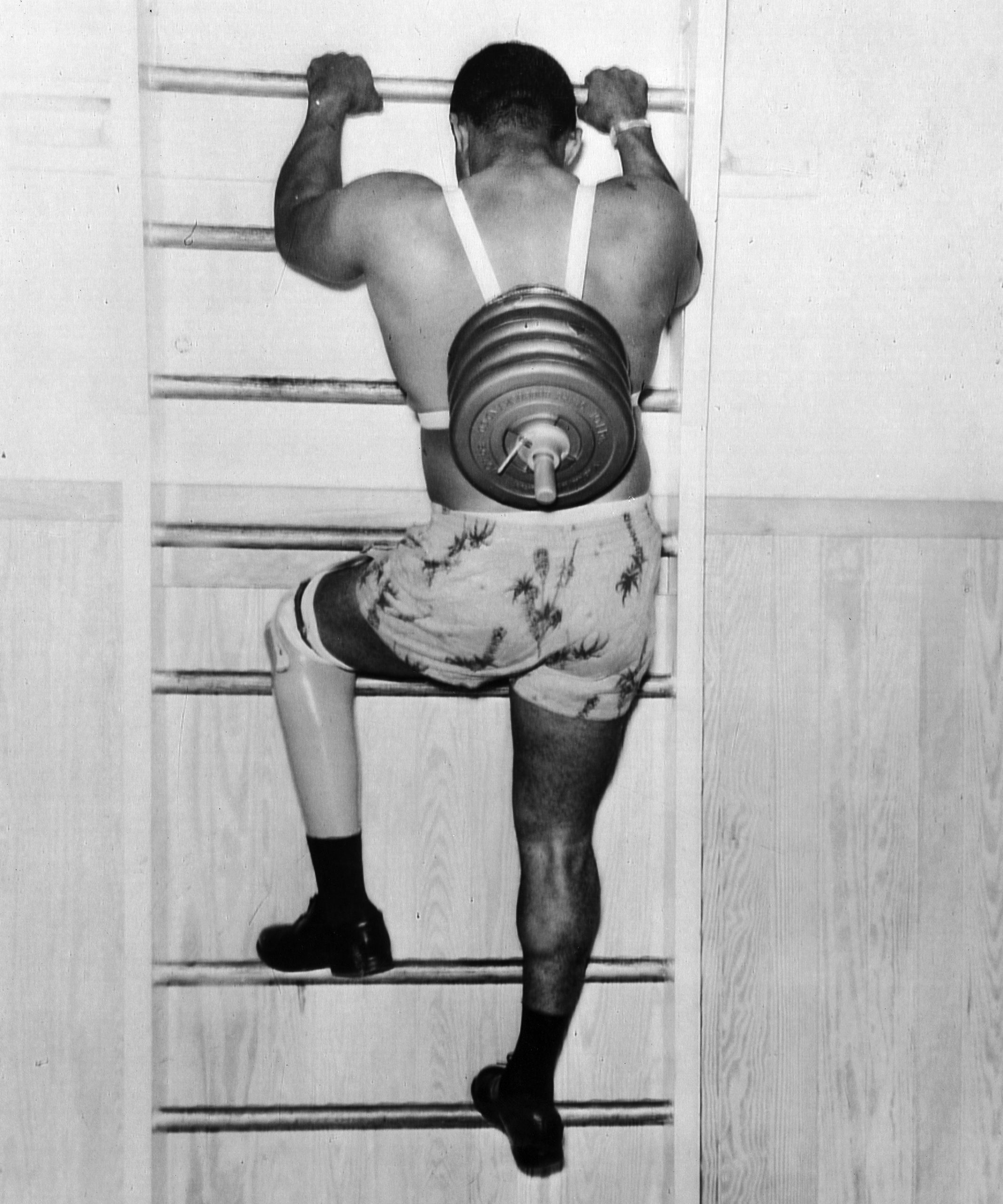

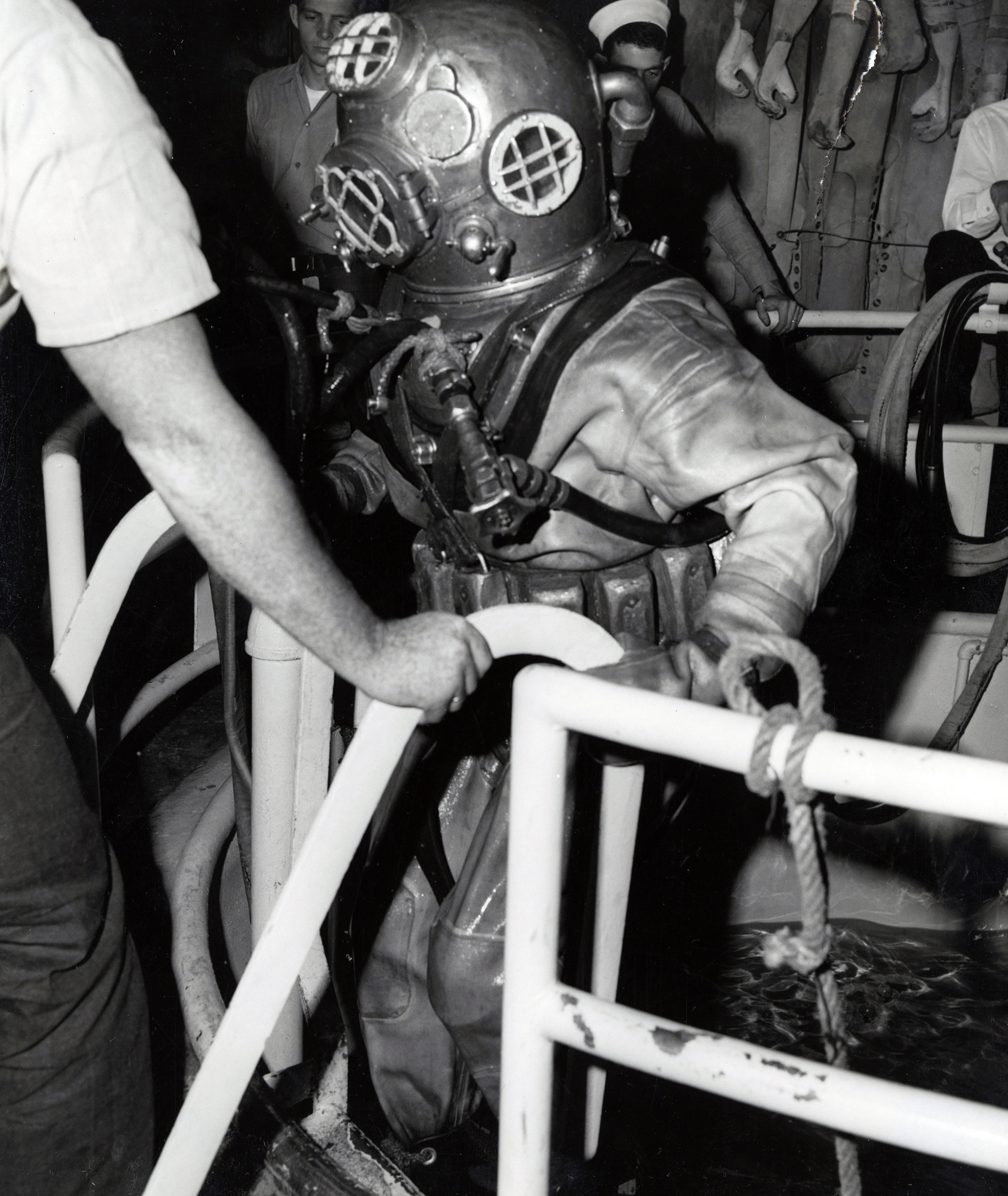

Axtell reluctantly agreed to let Brashear use the school’s diving facilities, knowing a mishap would ruin his career. Brashear dove in different diving systems — a MK V deep-sea rig, a shallow water diving suit, SCUBA gear — while a photographer took photos as proof of his competence.

The Bureau of Medicine and Surgery agreed to grant Brashear a trial period: he would be evaluated for one year at the Norfolk diving school to determine whether he could safely return to diving. The school’s new officer in charge, Chief Warrant Officer Raymond Duell, did not go easy on Brashear. (“That man dove me every day, every cotton-picking day,” Brashear recalled, “weekends and all.”) Brashear also led daily calisthenics for the other students, who didn’t realize he was an amputee and bemoaned his stamina.

At the end of the probationary year, he was restored to full duty as a Navy diver — the first time in Navy history for an amputee.

Brashear training with his prosthetic leg to climb diving ladders. The weights simulate the heavy MK V diving rig.

Brashear proving his diving aptitude post-amputation. Photo taken either at the Norfolk diving school or Deep Sea Diving School in Washington, D.C.

“Sometimes I would come back from a run [during the evaluation period], and my artificial leg would have a puddle of blood from my stump. I wouldn’t go to sick bay. In that year, if I had gone to sick bay, they would have written me up. I’d go somewhere and hide and soak my leg in a bucket of hot water with salt in it — an old remedy. Then I’d get up the next morning and run.”